More like a vault -- you pull the handle out

More like a vault -- you pull the handle outand on the shelves: not a lot,

and what there is (a boiled potato

in a bag, a chicken carcass

under foil) looking dispirited,

drained, mugged. This is not

a place to go in hope or hunger.

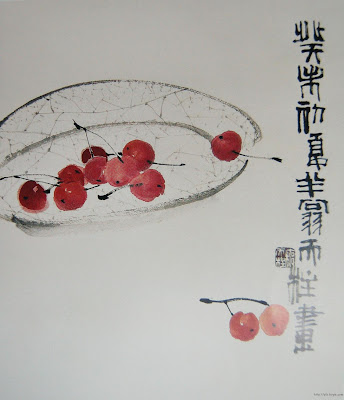

But, just to the right of the middle

of the middle door shelf, on fire, a lit-from-within red,

heart red, sexual red, wet neon red,

shining red in their liquid, exotic,

aloof, slumming

in such company: a jar

of maraschino cherries. Three-quarters

full, fiery globes, like strippers

at a church social. Maraschino cherries, maraschino,

the only foreign word I knew. Not once

did I see these cherries employed: not

in a drink, nor on top

of a glob of ice cream,

or just pop one in your mouth. Not once.

The same jar there through an entire

childhood of dull dinners -- bald meat,

pocked peas and, see above,

boiled potatoes. Maybe

they came over from the old country,

family heirlooms, or were status symbols

bought with a piece of the first paycheck

from a sweatshop,

which beat the pig farm in Bohemia,

handed down from my grandparents

to my parents

to be someday mine,

then my child's?

They were beautiful

and, if I never ate one,

it was because I knew it might be missed

or because I knew it would not be replaced

and because you do not eat

that which rips your heart with joy.

Thomas Lux

.jpg)