|

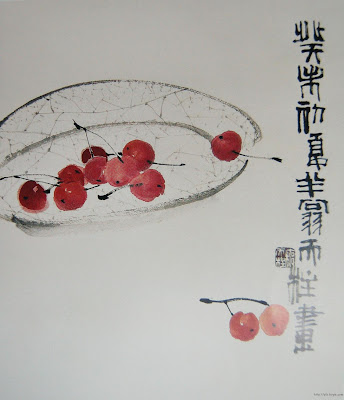

| Cherry - Qin Tianzhu |

500 g cherries

3 eggs

150g flour

150g sugar

10g yeast, prepared in warm water if necessary

100g butter

1 cup of milk

She placed the cherries in a buttered dish and looked out of the window. The children were racing across the lawn, Nicholas already between the clumps of red hot pokers, turning to wait for the others. Looking back at the cherries, that would not be pitted, red polka dots on white, so bright and jolly, their little core of hardness invisible, in pity she thought of Mrs Sorley, that poor woman with no husband and so many mouths to feed, Mrs Sorley who knew the hard core but not the softness; and she placed the dish of cherries to one side.

Gently she melted the butter, transparent and smooth, oleaginous and clear, clarified and golden, and mixed it with the sugar in a large bowl. Should she have made something traditionally English? (Involuntarily, piles of cake rose before her eyes.) Of course the recipe was French, from her grandmother. English cooking was an abomination: it was boiling cabbages in water until they were liquid; it was roasting meat until it was shrivelled; it was cutting out the flavours with a blunt knife.

She added an egg, pausing to look up at the jacmanna, its colour so vivid against the whitewashed wall. Would it not be wonderful if Nicholas became a great artist, all life stretching before him, a blank canvas, bright coloured shapes gradually becoming clearer? There would be lovers, triumphs, the colours darkening, work, loneliness, struggle. She wished he could stay as he was now, they were so happy; the sky was so clear, they would never be as happy again. With great serenity she added an egg, for was she not descended from that very noble, French house whose female progeny brought their arts and energy, their sense of colour and shape, wit and poise to the sluggish English? She added an egg, whose yellow sphere, falling into the domed bowl, broke and poured, like Vesuvius erupting into the mixture, like the sun setting into a butter sea. Its broken shell left two uneven domes on the counter, and all the poverty and all the suffering of Mrs Sorley had turned to that, she thought.

When the flour came it was a delight, a touch left on her cheek as she brushed aside a wisp of hair, as if her beauty bored her and she wanted to be like other people, insignificant, sitting in a widow's house with her pen and paper, writing notes, understanding the poverty, revealing the social problem (she folded the flour into the mixture). She was so commanding (not tyrannical, not domineering; she should not have minded what people said), she was like an arrow set on a target. She would have liked to build a hospital, but how? For now, this clafoutis for Mrs Sorley and her children (she added the yeast, prepared in warm water). The yeast would cause the mixture to rise up into the air like a column of energy, nurtured by the heat of the oven, until the arid kitchen knife of the male, cutting mercilessly, plunged itself into the dome, leaving it flat and exhausted.

Little by little she added the milk, stopping only when the mixture was fluid and even, smooth and homogenous, lumpless and liquid, pausing to recall her notes on the iniquity of the English dairy system. She looked up: what demon possessed him, her youngest, playing on the lawn, demons and angels? Why should it change, why could they not stay as they were, never ageing? (She poured the mixture over the cherries in the dish.) The dome becomes a circle, the cherries surrounded by the yeasty mixture that would cradle and cushion them, the yeasty mixture that surrounded them all, the house, the lawn, the asphodels, that devil Nicholas running past the window, and she put it in a hot oven. In 30 minutes it would be ready.

This is an extract from 'The Household Tips of the Great Writers' by Mark Crick, published by Granta Books.

Recipes (published earlier in Kafka's Soup) include: tiramisu as made by Proust; cheese on toast by Harold Pinter; clafoutis grandmère by Virginia Woolf; chocolate cake prepared by Irvine Welsh; lamb with dill sauce by Raymond Chandler; onion tart by Chaucer; rabbit stew by Homer; boned stuffed poussins by the Marquis de Sade; mushroom risotti by John Steinbeck; tarragon eggs by Jane Austen; Vietnamese chicken by Graham Greene and Kafa's Miso soup. Also included are recipes in the style of Jorge Luis Borges and Gabriel García Márquez.

No comments:

Post a Comment